I could give you a list of reasons why it’s been three months (!) since my last blog post, but that would accomplish nothing. The real reason I’ve been hiding – yes, hiding – is that I made a series of avoidable mistakes in a jacket that made me lose confidence in my abilities. Simply put, I was too embarrassed to post anything.

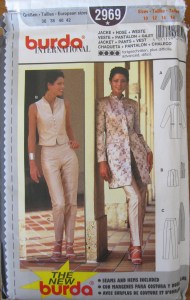

This episode has taught me that it is absolutely essential to check all assumptions and reinforce the basics no matter how far I think my skills have progressed. With a lot of encouragement from Sarah Veblen, I overcame the urge to allow the jacket to become yet another UFO and then worked with Sarah to correct the pattern mistakes I had made for a new version of the jacket. We also revised the collar pattern because the design needed some fine-tuning. The final step in this learning process will be to make the 2.0 version of the jacket. Before going on to that step, I want to share the experience to reinforce the lessons learned so that I don’t make the same mistakes again and, I hope, you will be able to avoid making them in the first place.

Back to Basics

First and foremost, test all assumptions. I made two muslins, so all the adjacent seamlines on the pattern pieces had been walked, right? Then how did I end up with a back piece that had a much longer shoulder seam than the one on the front piece? Obviously, I made an adjustment somewhere and didn’t recheck to make sure the adjacent seams matched before cutting out the fashion fabric. The thing that really got me is that the mistake wasn’t buried in a princess seam or something that took some time to check. The difference in the shoulder seams is something that hits you in the face when you lap the pieces over one another at the shoulder.

Lesson learned: keep track of all steps. The simple solution is to use a checklist before cutting the fashion fabric. I’m not doing this just when I’ve made changes to the pattern, but also when I pull different pieces from different garments. I might have made tweaks in a garment that I’ve forgotten about, so I can’t assume that the side front piece from one blouse will fit together with the front piece from another project. In this project, I started out intending to make three-piece sleeves, using the pattern from my still unfinished French jacket, but changed my mind and used the two-piece sleeves I’ve used for other jackets. It was only after I found myself struggling to ease in the sleeves that I realized the armscye for my French jacket is smaller than the armscye for my jacket sloper.

My new routine is to make a checklist with all the garment pieces and all the adjacent seams that need to walk. It looks something like this:

- Front to Side Front

- Side Front to Side Back

- Side Back to Back

- Front to back at shoulder

- Sleeve to armscye

When everything is checked off, I’m ready to cut.

Resist the Temptation to Combine Steps

When teaching patternmaking in her fit and design workshops, Sarah carefully lays out each step that her students should follow, which includes cutting the pattern on the cut line before walking adjacent pattern pieces. I thought this was a step I could skip and simply cut away excess paper when I used the pattern to cut fabric. I was wrong.

After I had kvetched to Sarah Veblen about all the mistakes I made with this jacket, I worked on fixing each of the problems in a workshop that she calls “You Choose Your Focus,” where each participant works on whatever she needs to accomplish with Sarah’s supervision. As Sarah watched me walk two pattern pieces, she noticed that I had veered off from the seamline on one piece and was walking one seamline onto a cut line. She assured me that this is not an uncommon mistake, especially when changes have been made to the pattern and there are extra lines and markings that have been crossed out. She then said in her gentle, patient and non-accusatory manner that the best way to avoid this mistake or at least minimize the number of times you make it is to trim away the excess pattern paper before walking the pattern pieces.

Lesson learned: If a step seems unnecessary, ask the instructor why she advises taking that step before skipping it.

Don’t Forget to Think Seamline

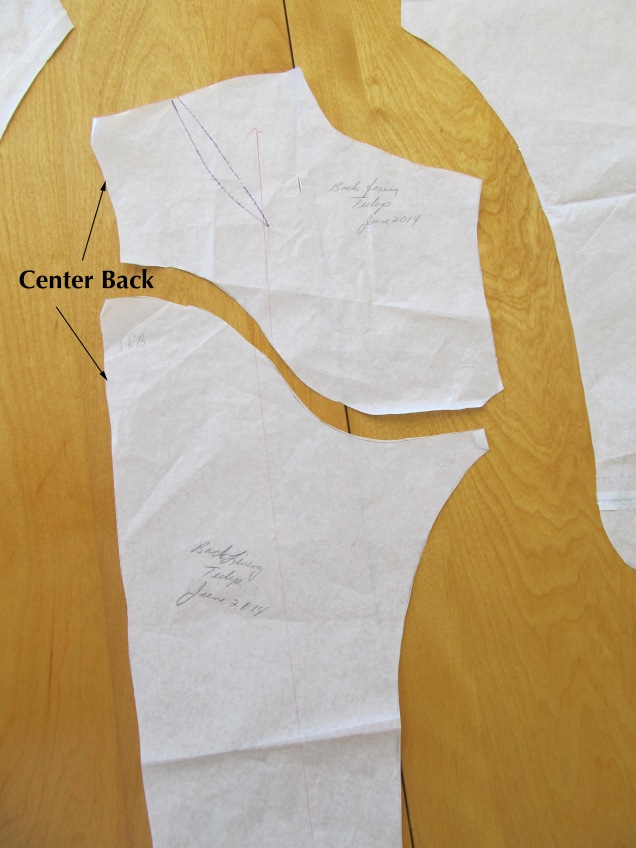

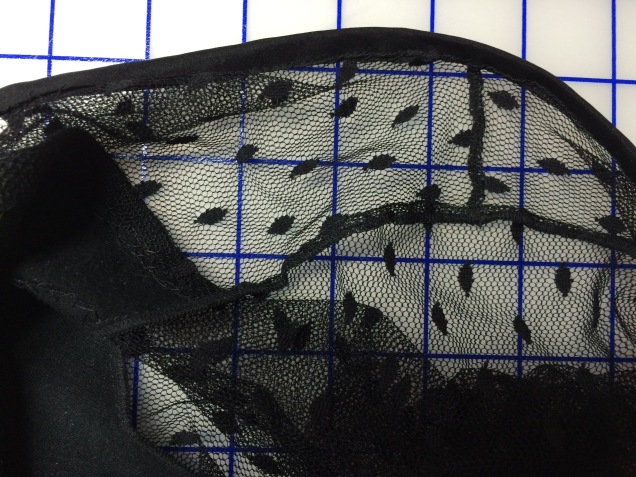

This is another place where the number of lines on a pattern piece can cause confusion. Some lined garments are lined to the edge, whereas others have linings that hang from a facing at the neckline and other really ambitious garments have both a neck facing and a faced hem with a lining in between. Here is what that looks like on this particular jacket:

The facings are made of a beautiful black silk taffeta that has a tone-on-tone embossed rose pattern. Sigh. The silk lining is from A Fabric Place outside of Baltimore and I managed to buy more when I was there in November. Yea.

So, on my first attempt to make the lining pattern I marked the depth of the facings on the garment pattern pieces, plus cut lines above and below each of those seamlines, which meant I had three sets of lines at the top (seamline, then cut line for lining and another cut line for the facing), plus two at the bottom, since the lining and hem facing don’t get attached as a seam but have a jump hem instead. I also got mired in math trying to figure out the depth of the jump hem, which is why you see that seam at the bottom of the lining in the picture above. That’s where I attached a bias strip to add length.

Sarah’s advise is to only draw the seamlines, or if you must draw multiple lines, color code them. She draws her seamlines in blue pencil.

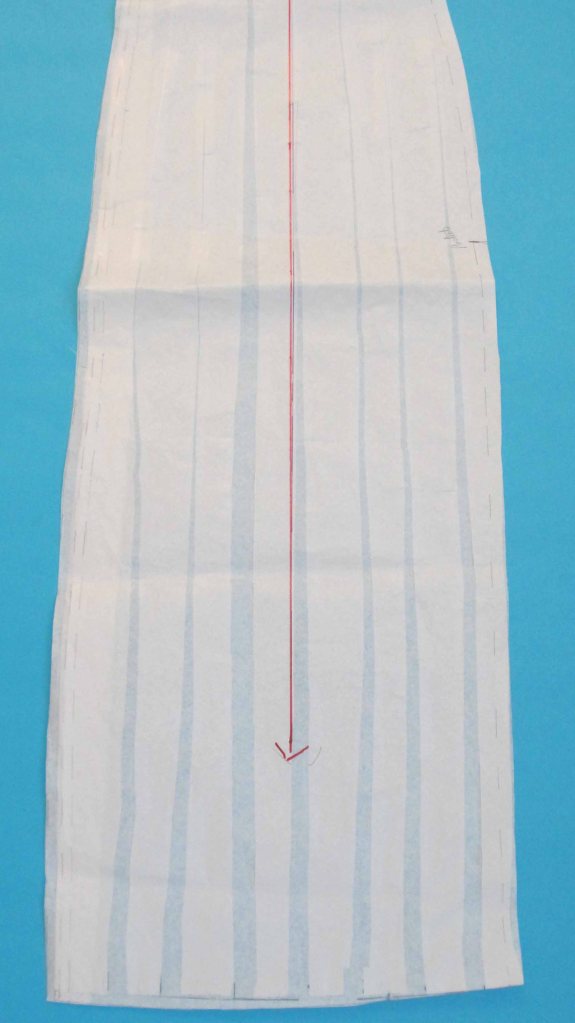

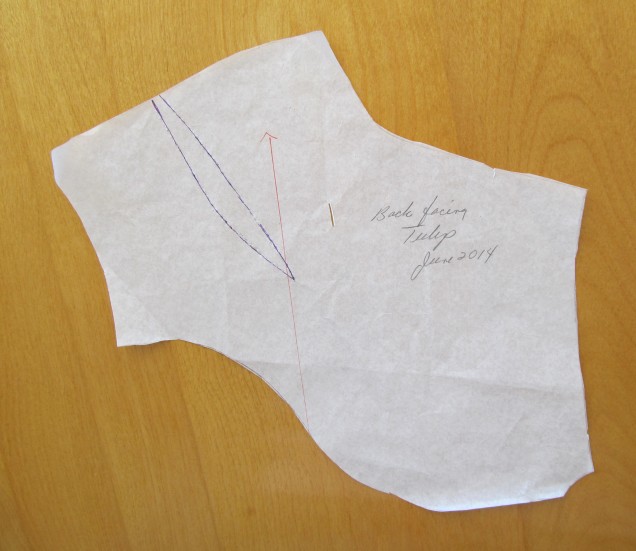

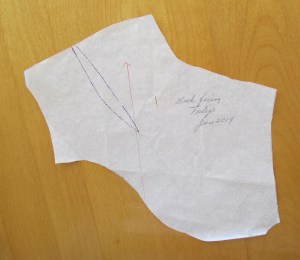

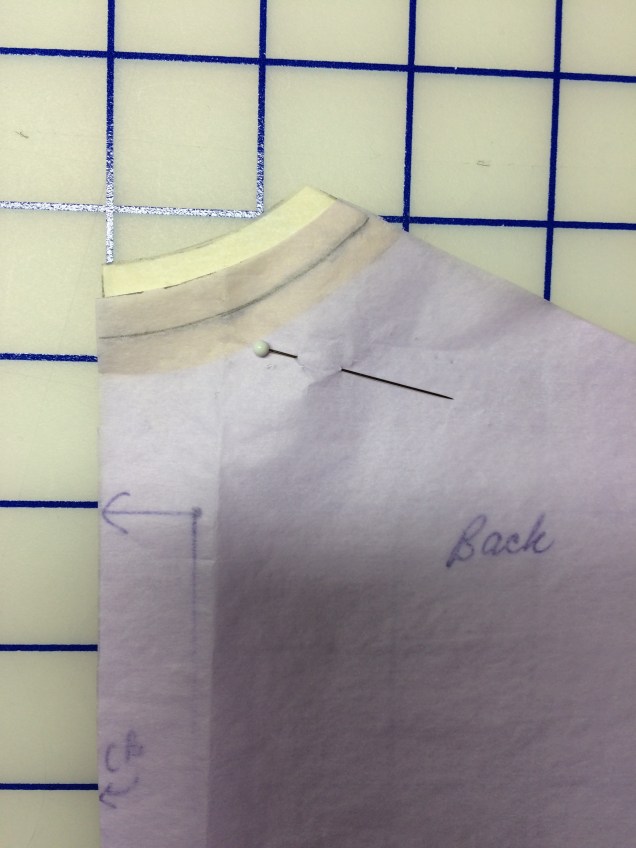

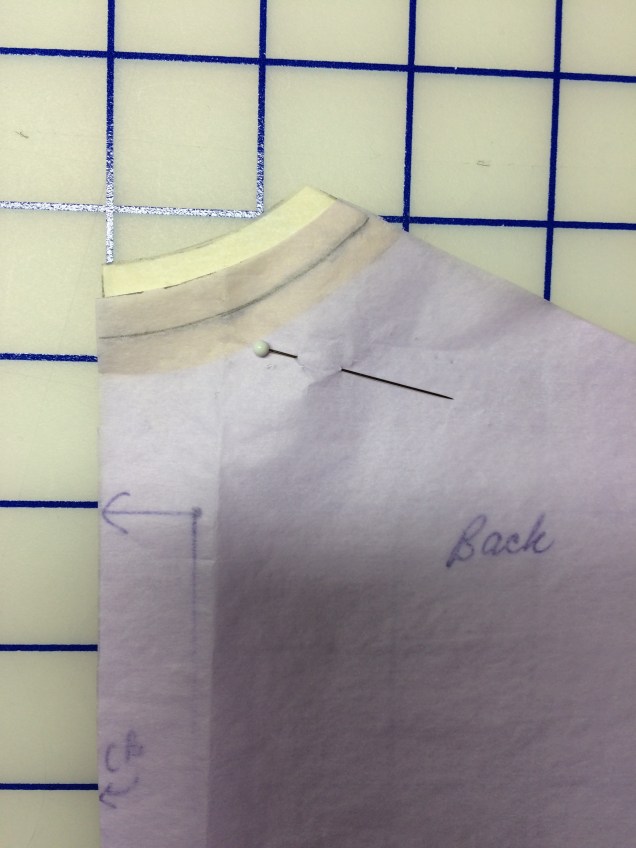

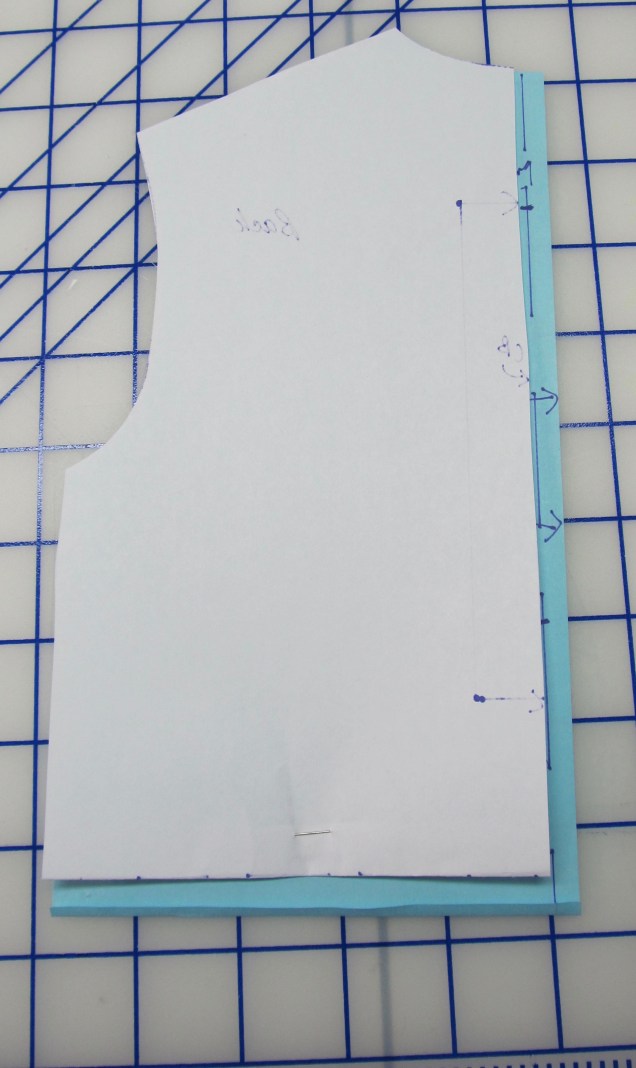

Here is a visual for the neck facing/lining segment of that convoluted explanation:

The reduced scale pattern piece for the garment back is on white paper. I’ve marked only the seamline where the lining (purple tissue paper) attached to the facing (yellow tissue paper). As you can see, the lining’s seam allowance extends up like it’s supposed to and the facing seam allowance extends down. The process was to mark only the seamline, then draw the facing piece, add the seam allowance and cut, then draw the lining piece, add the seam allowance and cut.

Lesson learned: Pattern pieces that get too cluttered are confusing and it’s a mistake to think I will always be able to remember which piece goes up and which goes down.

The whole jump hem thing is a little more involved, so it gets its own section.

Map Out Jump Hems Visually

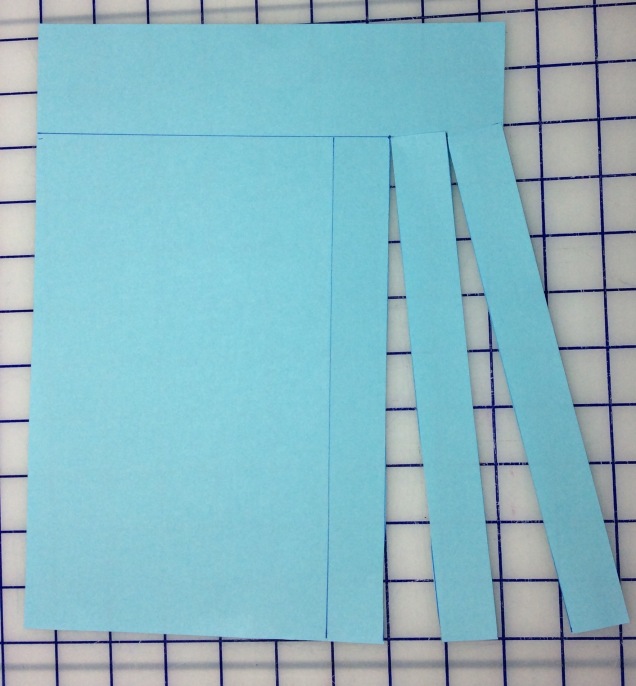

You don’t have to be math-challenged for math to trip you up, at least I don’t. And there’s something about jump hems that have had me confused for a long time. Sarah walked me through the process visually with strips of paper and I think I finally get it.

When a jacket is lined to the edge (no neck facing) and the hem is turned up (no hem facing), the lining pattern pieces are the same length as the fashion fabric pattern pieces. To get a nice jump hem that covers the hem stitches and ensures that the fashion fabric isn’t pulled up by a too-short lining, we build in a jump hem, which simply means that the fabric hangs down part way over the hem allowance, has a soft fold, comes back up to the hem stitching line and is hand stitched in place. Sarah advises to turn the raw edge of the lining under by ¼” and pin that fold to the hem stitching line and then stitch. Everything works out just fine.

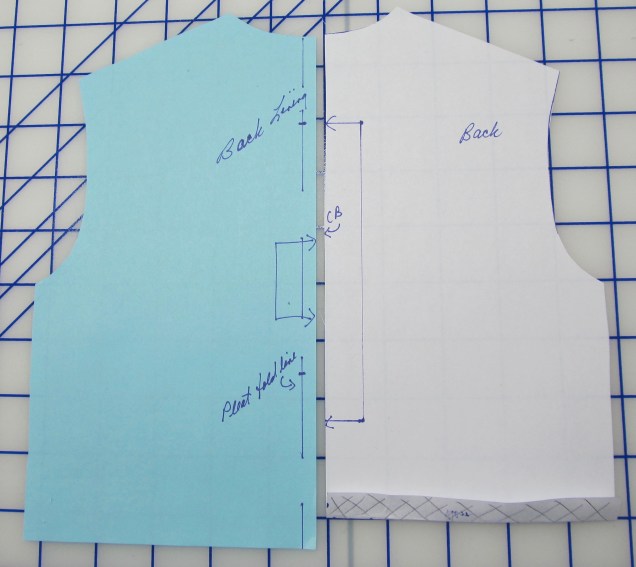

Here is an attempt at a visual representation of how that works:

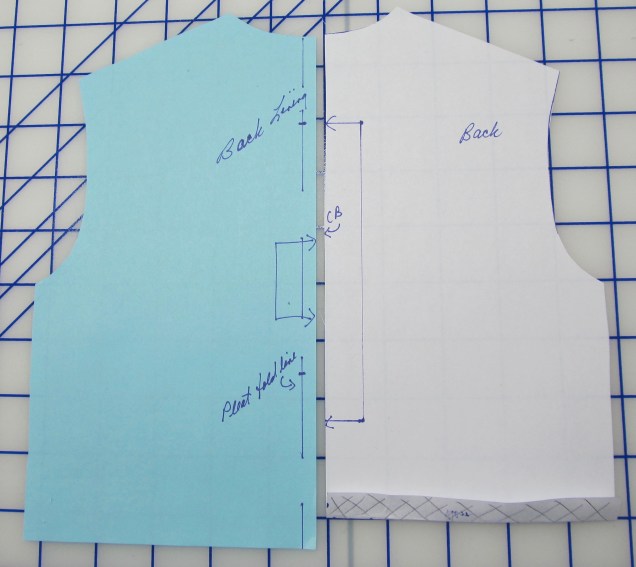

The blue paper simulates a back lining for a jacket that is lined to the neck edge. It is the same length as the back jacket piece. The only difference is that it has a little extra width to allow for a pleat at center back and it is marked in approximately the places where the stitching ends to allow for arm movement. The white paper represents the fashion fabric pattern piece, which is turned up at the hem with cross-hatching to represent the right side of the fabric in the hem allowance.

The picture above shows the fashion fabric piece with the hem turned up overlaying the lining piece, which has ¼” turned up at the hem edge.

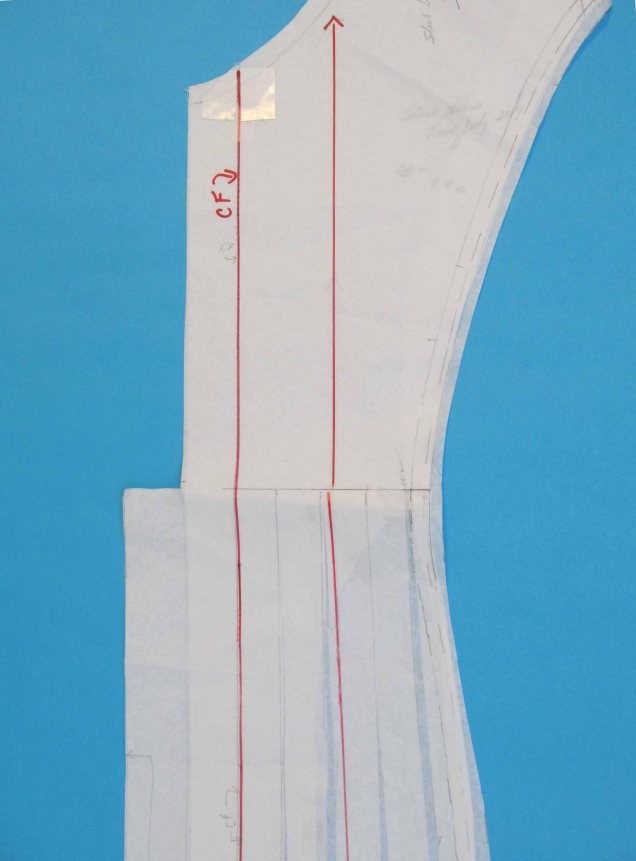

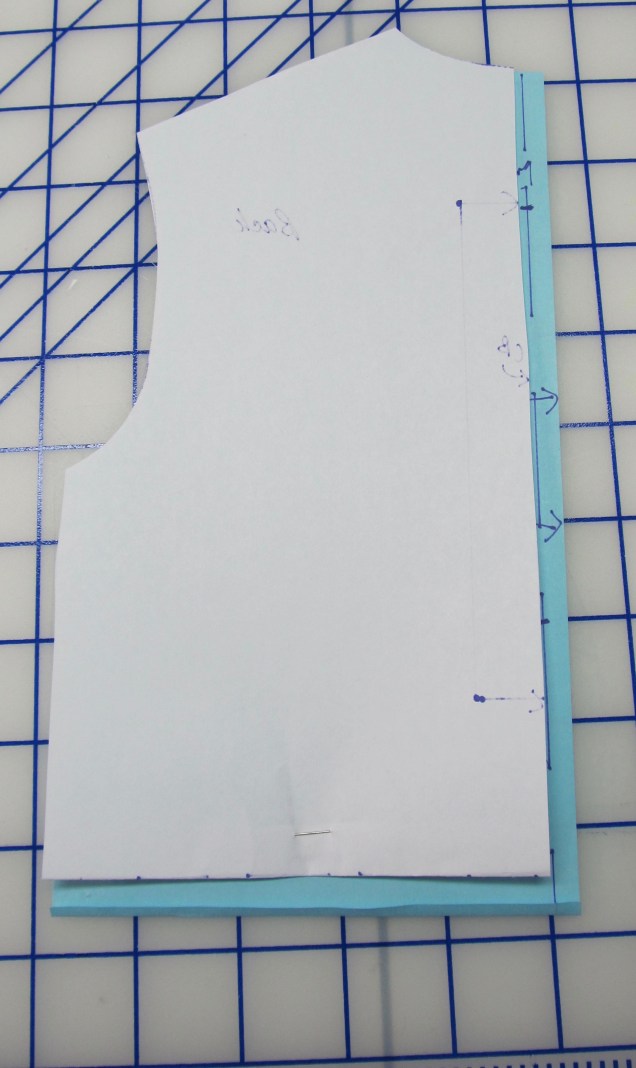

The rest of the pictures show mock-ups of a jump hem with a lining, neck facing and faced hem. The principles are the same. The only difference with the faced hem is that you want a bit more of the facing to not be covered up by the lining.

Here we have the lavender tissue paper as the lining (it worked much better than the stiff blue paper I used earlier), plus the yellow tracing paper showing the facings at the neck and hem. I’ve turned the lining under ¼” and pinned it to the top edge of the hem facing. Notice the fullness above the area that’s pinned.

Here it is with the lining tissue smoothed down. Try to ignore that hemline that I drew in. Obviously, I misjudged where this would end up, which is why this method is better than doing the math.

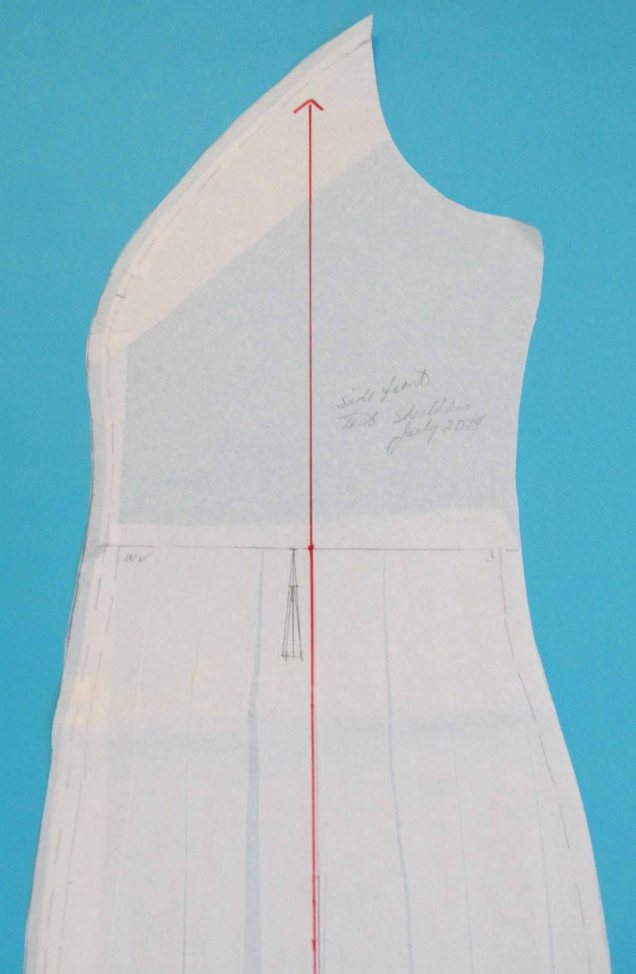

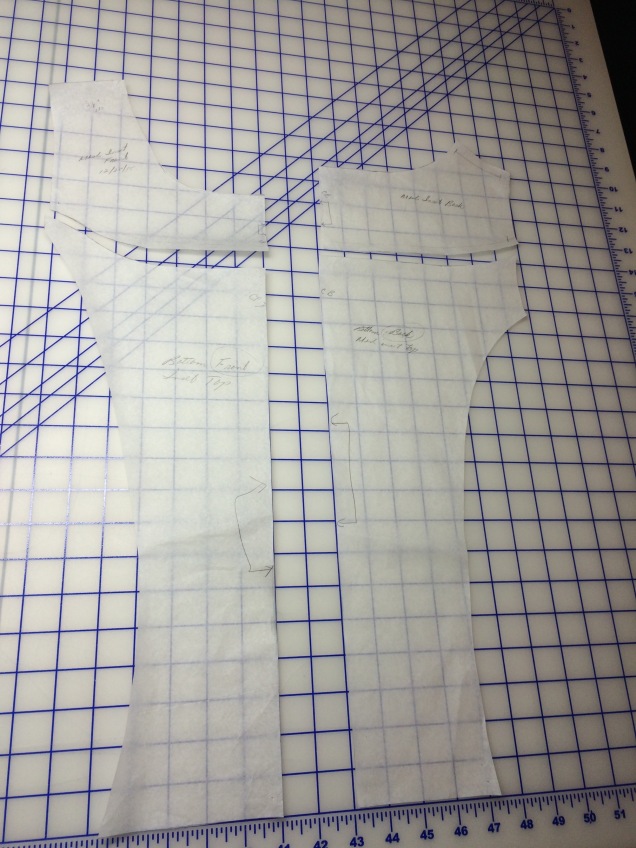

Here is a view that tries to show everything that’s going on in the area under the jump hem that is hidden when you see a sewn sample.

Lesson learned: Visual mock-ups can avoid a whole bunch of stress and can sometimes clarify things that were once a mystery.

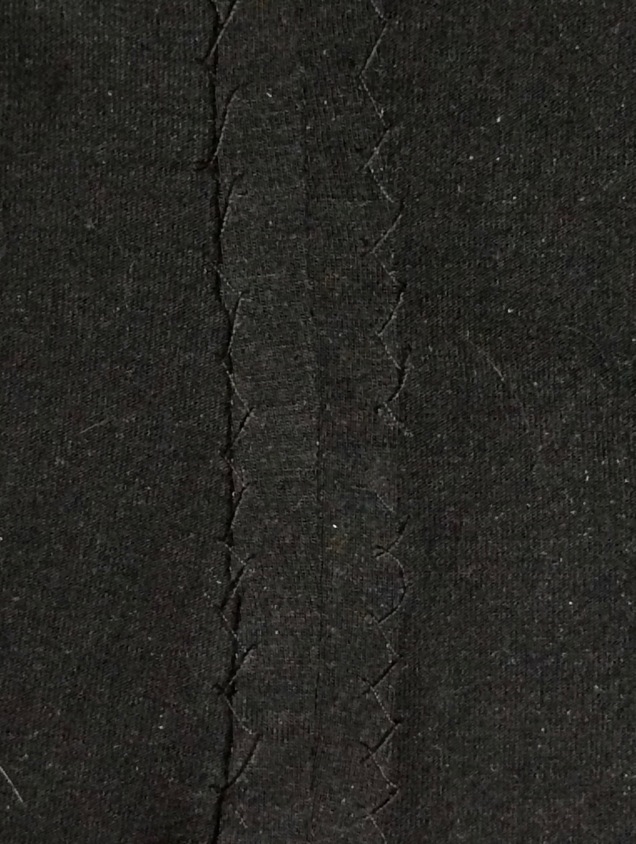

Resewing Has Its Limits

Not all of the problems I encountered were in the pattern. I made some plain, vanilla sewing mistakes that gave me quality time with my seam ripper. There was a snowball effect to this, which I encounter quite a bit. Once I make one dumb mistake I seem to make a whole slew of them. One example was that I set the collar with right sides together. Very dumb. Ordinarily, sewing mistakes are easy to fix, assuming you haven’t trimmed or clipped anything yet. But the lovely silk and wool blend fabric I used for the jacket raveled an unbelievable amount when handled. No matter how careful I was in removing stitches, I was left with very little seam allowance in many areas. It makes me worry about the jacket falling apart when I wear it.

Lesson learned: check the big picture before sewing a seam. Just because the pieces went together nicely when pinning doesn’t guarantee that they are oriented correctly.

There’s More, But It Can Wait

I also learned that my understanding of collars and undercollars had some gaps. We can walk through that in a later post once I’ve gotten comfortable employing my new knowledge on the subject. Besides, I’m more than ready to stop dwelling on my disappointment and move on to some successes.

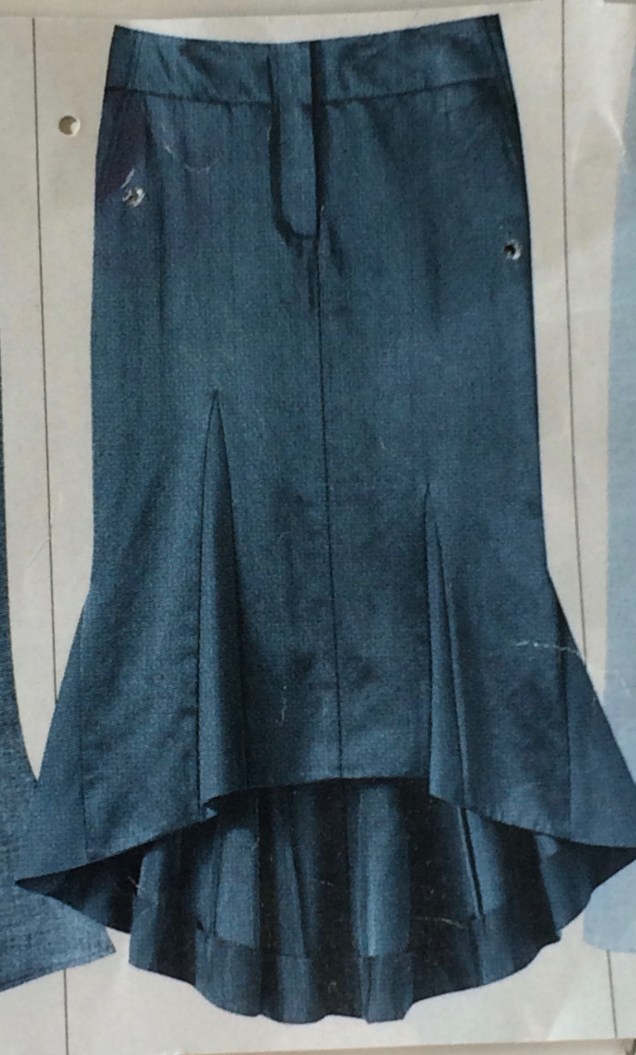

Here is what the jacket looks like. I finished it in time for the Sew Chicago holiday brunch. Everyone was very supportive and had nice things to say about it and I know that if I hadn’t blabbed about all the mistakes I made most people would never have noticed. I’m looking forward to getting the 2.0 version of it done and feeling really good about the work.

The invisible thread I like to use is

The invisible thread I like to use is

Reading

Reading