Frankenpatterns is a word that some sewists are using to describe projects they make by combining elements of two or more patterns. I have some issues with the term. First, this isn’t anything new. I know there are some experienced sewists who never deviate from a pattern, but many of us have been pulling details from one pattern and grafting them onto another without thinking we were doing anything out of the ordinary. A case in point is this two-piece dress that I made by combining my sloper, or basic fit, bodice pattern and the neckline and collar from Vogue Pattern 8667.

FYI, the collar is just a rectangle cut on the bias. The pattern doesn’t say to interface it but I always interface my collars and I think it helped with this one.

FYI, the collar is just a rectangle cut on the bias. The pattern doesn’t say to interface it but I always interface my collars and I think it helped with this one.

I also used the same neckline for a black silk two-piece dress with no sleeves and no collar.

The other problem I have with Frankenpatterns is the name itself. When patterns are combined well, I don’t think the results are monstrous at all. As an example, here is the first jacket I made from my sloper.

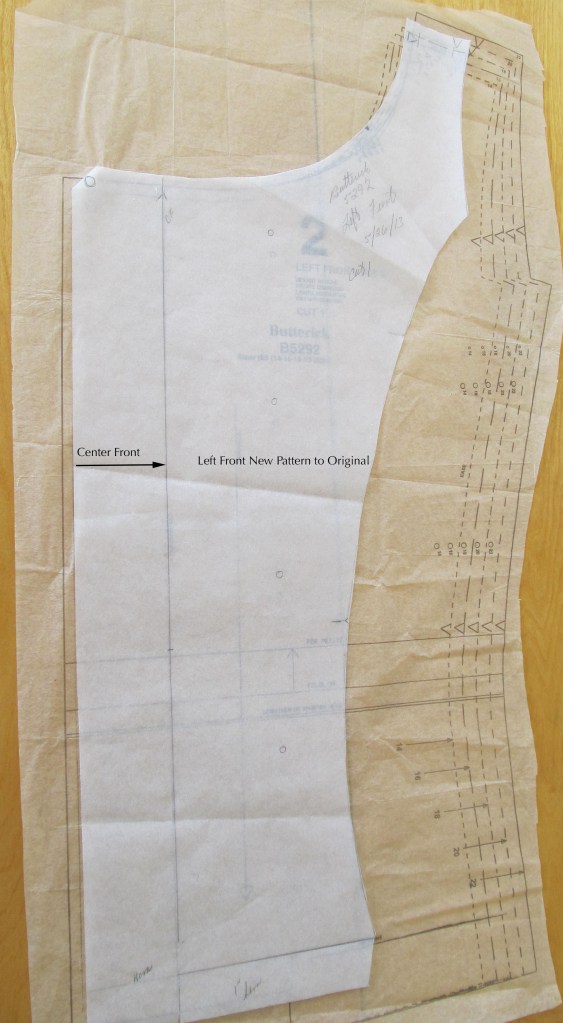

The pattern I used is out of print, Butterick B5292.

The pattern I used is out of print, Butterick B5292.

This was my first attempt to apply my sloper to a pattern in a way that required more than just a bit of tweaking. I have to say that when I first placed the sloper pieces on the main pattern pieces, I was intimidated.

This was my first attempt to apply my sloper to a pattern in a way that required more than just a bit of tweaking. I have to say that when I first placed the sloper pieces on the main pattern pieces, I was intimidated.

Here is what one of the front pattern pieces looks like with my jacket sloper on it.

I made this jacket before I made the basic jacket pattern you see here so the contrast was even greater at the time. I also didn’t have a full set of helpful landmarks on my bodice sloper at the time. All I had marked was Center Front and Center Back, which I knew I had to line up with the corresponding landmarks on the commercial pattern. Since then, I’ve added a bustline and waistline on every piece by marking them on the front and then walking the adjoining seams to get them to connect at the same level all the way around. Had I done that to my sloper at the time and made corresponding markings on the commercial pattern, I might have felt more confident.

I made this jacket before I made the basic jacket pattern you see here so the contrast was even greater at the time. I also didn’t have a full set of helpful landmarks on my bodice sloper at the time. All I had marked was Center Front and Center Back, which I knew I had to line up with the corresponding landmarks on the commercial pattern. Since then, I’ve added a bustline and waistline on every piece by marking them on the front and then walking the adjoining seams to get them to connect at the same level all the way around. Had I done that to my sloper at the time and made corresponding markings on the commercial pattern, I might have felt more confident.

Because this is an asymmetric jacket, there was a lot to be added beyond Center Front. I used my own side front and side back pieces and my own sleeve pattern, so I didn’t have to worry about any of the differences on the other side of Center Front.

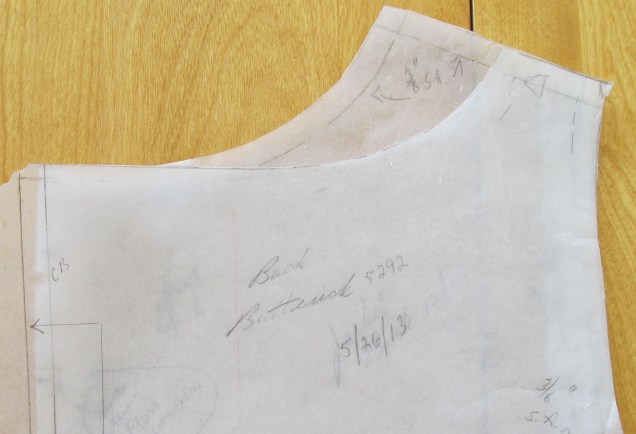

I don’t have a tapered back seam in my bodice or jacket patterns, but the commercial pattern does. I wanted to lay out the back piece on the fold, so I lined it up with the marked Center Back and ignored the tapering in the pattern. So, I was able to ignore everything that was going on on either side of Center Back. I just needed to use Center Back as a point of reference.

As you can see, my sloper is quite a bit shorter than the pattern. I’m average height (5’5″ and a bit). Pattern grading increases both horizontally and vertically. If only that were true with changes in people.

Basically, the only things I needed to figure out were the distance between the shoulder point and a line extending up from Center Front on the front piece and the corresponding distance from Center Back on the back piece. Then I needed to draw in my shoulder seams at my correct angle and stop where I needed to stop in order to come out with a neck seam that was the same length and shape as the neck seam on the commercial pattern. I also needed to make sure that the shoulder seam is the same length in the front as it is in the back.

Here is how my drafted pattern looks overlaid on the commercial pattern.

I was a little concerned about how short the shoulder seams are, but I wasn’t feeling confident enough to change the neckline and create accurate corresponding changes to the collar stand. When I was sewing the jacket I thought that was a dumb decision because my bra straps might make unscheduled appearances. The next time I make this jacket, I’ll bring in the neckline just a bit and make the corresponding change to the collar stand.

I was a little concerned about how short the shoulder seams are, but I wasn’t feeling confident enough to change the neckline and create accurate corresponding changes to the collar stand. When I was sewing the jacket I thought that was a dumb decision because my bra straps might make unscheduled appearances. The next time I make this jacket, I’ll bring in the neckline just a bit and make the corresponding change to the collar stand.

If the seamlines in these pictures look narrow to you, it’s because I like to use 3/8″ instead of 5/8″ seamlines. Only recently I’ve switched back to 5/8″ for sleeves and armscyes because of the method I use for setting sleeves. Yes, it does seem my sewing gets unnecessarily complicated sometimes, but I really do have reasons for these choices. The other odd marking you see on the back pattern piece is the extra Center Back foldline. This is actually a shortcut so that I can use one pattern piece for both the fashion fabric and the lining and still get that pleat in the center back of the lining.

Here is what my pattern for this jacket looks like when compared to the jacket sloper.

And here is the finished product on my dress form.

The fabric is a silk suiting that was lovely to work with and is a delight to wear. But, the jacket could have used more structure. I lined it to the edge in a silk charmeuse print, but with the hidden snaps leaving impressions on the fabric, a front facing would have been a better choice. Still, I love wearing it. And I don’t think it bears any resemblance to a monster.

The fabric is a silk suiting that was lovely to work with and is a delight to wear. But, the jacket could have used more structure. I lined it to the edge in a silk charmeuse print, but with the hidden snaps leaving impressions on the fabric, a front facing would have been a better choice. Still, I love wearing it. And I don’t think it bears any resemblance to a monster.

The first time we talked on the phone I learned that Sarah was working on her book,

The first time we talked on the phone I learned that Sarah was working on her book,